Joe Pittman: Breaker of Horses and Gender Stereotypes

By Erin Rosson

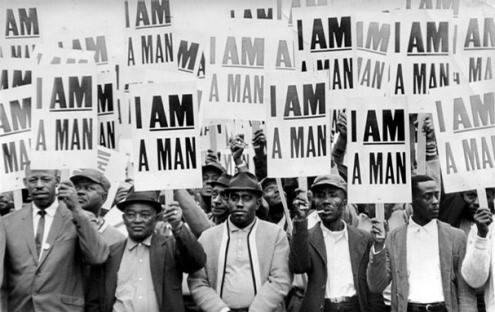

Historically, the masculinity of Black men in America has been devalued or altogether withheld, thus resulting in a higher difficulty in achieving the status of manhood that is so readily applied to White men. Under the institution of slavery, Black men were not considered human, and therefore could not achieve the status of “manhood.” The only way Black male slaves could achieve any semblance of masculinity was through their status as laborer, a status where the markers of effective labor were determined through the laborer’s animalistic qualities. Unfortunately, this only worked to further dehumanize Black men while tying their worth to animalism. The proliferation of this stereotype within society produced a double-edged sword for Black men. On the one hand, the more animalistic the Black man’s behavior was, the more masculine he was considered. On the other hand, manhood was defined through the White man, so the Black man could never be truly considered a man because his masculine laboring qualities were considered too animalistic. This double-bind and the animalistic Black male stereotype bleed into all aspects of society, including within American literature, even unfortunately extending into the genre of slave narratives, many of which were written by formerly enslaved Black males.

The civil rights era provided the Black community with the drive to question dangerous stereotypes within the broader culture. Neo-slave narratives, a genre that grew out of the civil rights era, was one major literary genre that allowed Black authors to question stereotypes of Black masculinity within popular culture. Ernest Gaines, as a Black man who grew up in the deep South during the early 1900s, undoubtedly personally experienced the double bind of Black masculinity. Gaines wrote The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, one the earliest neo-slave narratives, at the tail end of the civil rights era, so the way he wrote the book’s male characters reflect his personal experiences as well as the growing attempt to problematize stereotypes of Black masculinity.

Particularly, Gaines’ characterization of Joe Pittman reflects a questioning of the stereotyping and dehumanization of Black men because Joe Pittman, viewed through the eyes of the narrator Jane, is a three-dimensional humanized man. Joe Pittman, who is the husband of Jane, is a horse-breaker who works for White men during Reconstruction. Joe is a very skilled breaker, and he is valued for his adeptness with animals. In fact, most of the characters who come into contact with Joe view him as a “manly” man specifically because of his ability to break any horse, even the wildest stallion. This tying of Joe’s masculinity to his animalistic qualities as well as to literal animals reflects the dehumanizing stereotype that was prevalent in slave narratives. Joe’s character initially seems to play into stereotype, but Gaines actually subverts this idea through Jane’s views of Joe.

The most notable scene to this point involves a hoo-doo lady, Madame Gautier, whom Jane visits in order to save Joe from being killed by a black stallion. Prior to this scene, Jane had experienced multiple dreams in which Joe was killed trying to break the stallion, and despite her best efforts to warn Joe of the danger, he refused to listen. The hoo-doo scene revolves entirely around Madame Gautier’s refusal to see Joe as someone separate from the stereotype of an animalistic man. Jane attempts to push back against Gautier’s assertions by claiming Joe is a real man regardless of his ability to break horses, thus pushing back against the animalization and affording Joe manhood and humanity. Essentially, Jane’s point of view transforms Joe from the animalistic stereotype to a fully dimensional man, someone who has flaws unrelated to his race as well as masculine qualities that have nothing to do with his ability to labor.

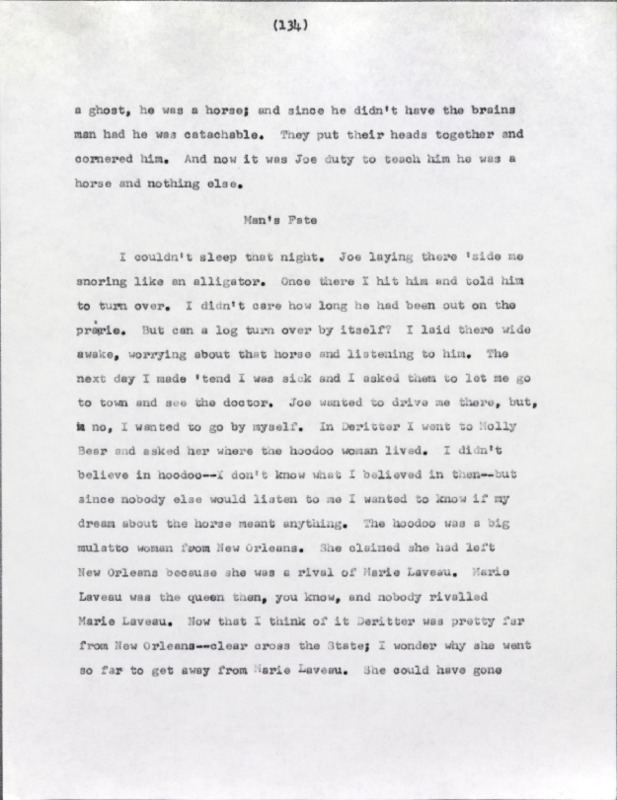

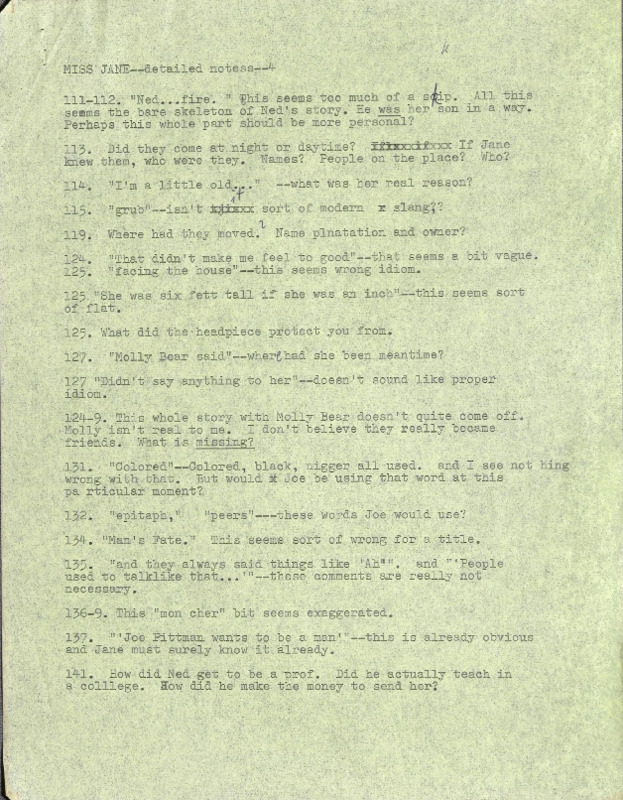

However, in looking through the archives in the Ernest J. Gaines Center, it is clear that Gaines was initially attempting to make this point even more salient. In one of the earliest typed drafts, the title of the chapter containing Madame Gautier’s scene was “Man’s Fate,” not “Man’s Way” as in the final draft. “Man’s Fate” can be taken in a few ways. Most obviously, it could be alluding to Joe’s death at the end of the chapter. Less obviously, by including the word fate, Gaines could have been thinking in line with the fate all Black men suffered in the south, a fate of denied masculinity except as tied to their animalism. Gaines changed the title after his editor, in notes also found in the archives, pointed out that the original, “seems sort of wrong for a title.”

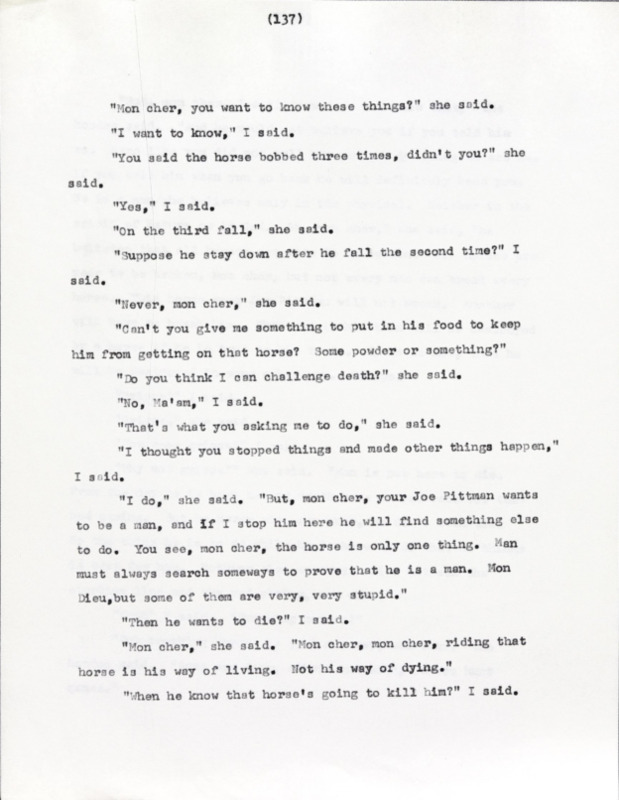

Also notable, In the earlier draft, Gaines draws out the conversation between Madame Gautier and Jane, with more focus on Joe Pittman’s masculinity and his role as a horse-breaker. Two important lines in this earlier draft are spoken by Madame Gautier: “your Joe Pittman wants to be a man . . . riding that horse is his way of living. Not his way of dying.” Both of these lines are removed by the final draft of the novel. Importantly, Gaines’ editor, within these same notes, also asserted that Gaines did not need to have Gautier explicitly state that Joe wanted to be a man because that statement was already inherently obvious to both the reader and Jane. However, just like the other characters in the book, the editor here seemed to misread Joe’s character as necessarily falling in line with dehumanized, animalistic stereotypes.

The editor’s comment essentially summarizes Joe’s entire characterization as defined through his manhood. What the editor missed here is the historical importance of Black men’s masculinity, as discussed at the beginning of this article. By stating that it is obvious Joe wants to be a man, the editor failed to understand Gaines’ importance in pointing out Joe’s intentions as a way of highlighting and questioning historical stereotypes of Black manhood. Since Joe is a Black man living in the time of reconstruction, he would have been faced with dehumanization and a societal refusal to see him as a “man.” This drawn-out conversation between Gautier and Jane deals not just with Joe’s masculinity, but also with his humanity, and is therefore crucial to understanding the plight of a Black man in the South.

The editor also misunderstands Jane’s character and characterization of Joe. Jane would understand Joe’s want to be defined as a man since she lived during the time of slavery and reconstruction and would have been exposed to the dehumanization and emasculation of Black men. However, Jane’s arguments in this scene are not in support of the obvious nature of Joe’s need to be a man, but rather focus on his already being a man because of his good, non-animalistic qualities. By reviewing the changes between Gaines’ early draft and the final version of the novel, it becomes clear that this editor’s notes led Gaines to change the Gautier conversation to focus less on Joe’s specific need to be seen as human, to a focus on the general way of men’s pursuit of masculinity.

Fate is more apt to what Gaines seems to be trying to get at in this early draft; namely, the fate many Black men face when having their humanity deprived through a refusal to recognize their manhood unless they pursue hyper-masculine animality. In the final version of this chapter, after Gaines made the editor’s recommended changes, the focus moved more to the way all men act regardless of race, thus taking the focus off the importance of the fate being forced onto Joe. The historical implications of Black masculinity are still present in the final draft, but they are tamped down and denied a spotlight, much like Black manhood. Instead, the spotlight becomes Joe’s foolishness, putting the onus for his death more on Joe’s “way” of living rather than the “fate” the racist structuring of society that refuses to acknowledge a Black man’s humanity forces upon Joe.

Endnotes:

Jordanna Matlon, "Black Masculinty Under Racial Capitalism" (2019).

Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, “Losing Manhood: Animality and Plasticity in the (Neo)Slave Narrative” (2016).