Reversing Slavery's Religious Oppression

By Camille Duhon

The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman by Ernest Gaines is one of the most well-known neo-slave narratives of the 20th century. Written during the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement, the novel takes on themes that were common in antebellum slave narratives and reclaims the various forms of oppression that slaves were both aware and unaware of. One of the biggest themes: Religion.

Religion has always had its place cemented in the history of antebellum slave narratives as some saving grace. However, religion wasn’t originally meant to be a form of salvation for enslaved men and women. As Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene D. Genovese point out in “The Divine Sanction of Social Order: Religious Foundations of the Southern Slaveholders’ World View,” religion, specifically Christianity-based religions like Catholicism and Protestantism, was more like a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Slaveowners didn’t introduce religion to their slaves in order to spread the good news from the good of their hearts. They were doing it to preserve what they believed was their right to own slaves. This is highlighted in the writings of southern theologians from the 1800s, most notably those of James Henley Thornwell, who supported the view that slavery was God-ordained and demanded a social order that defended and upheld the institution. This refusal of the separation of church and state often led to slaveholders introducing Christianity and Protestant beliefs to their slaves with the hope of instilling obedience into their consciousnesses. Many slave narratives of the mid-1800s, written by those who were unaware of this sinister tactic, therefore highlight religion as a saving grace. To those along the lines of Frederick Douglass, Thomas Lewis Johnson, and George Henry, religion was simply salvation instead of a devious trick.

Ernest Gaines' use of religion in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman doesn't hide the danger lurking in religion; instead, he shines a light on that hidden danger in multiple situations throughout the novel. Of all the instances of malicious religious symbolism in the novel, the most powerful one is through the moments that the reader spends with Joe Pittman. Joe is introduced as one of the most important people in Jane’s life. She tells the interviewer writing her story that whenever Joe was killed, “a part of me went with him to his grave. No man would ever take his place, and that’s why I carry his name to this day.” This is an incredible section of the novel because it’s one of the only instances where Jane is truly vulnerable about her feelings. This relationship is brilliantly crafted by Gaines because it not only shows the reader a deeper glimpse into who Jane is and what her motivations were at this point in her life, but it also leads the reader to get attached to the couple and root for them to succeed. Whenever the pair is able to leave the plantation they had been working on, there is a false sense of security that forms around them; we end up believing that, although they had to struggle to pay and leave the plantation, they’ve finally been able to break free and make lives for themselves on their own time and with their own money. Throughout their journey to and life at their new home, Jane goes to great lengths to care for and protect Joe from any sort of harm that could befall him – including visiting a Hoodoo woman in an attempt to prevent his inevitable demise.

In “Man’s Way,” Jane travels to a Hoodoo practitioner named Madame Gautier in order to protect Joe from what she believes will end up being his death: A black stallion that he’s supposed to break and get ready for sale. The introduction of the horse itself is rooted in malicious symbolism; Jane immediately assumes that it’s an omen of death, a Devil, an object that had been haunting her nightmares for a long time. This framing of the horse as the Devil in and of itself is a reversal of religious salvation. For once, the religious symbol is one of death and destruction instead of life and salvation. When Jane meets with Madame Gautier, she receives a small vial of powder that she is told by Gautier would prevent Joe from getting on the black stallion and keep him from dying. Jane returns to her home, doesn’t use the powder, and Joe Pittman ultimately dies in the way she knew he always would: Trying to break the black stallion.

The very fact that Jane visited a Hoodoo woman for help is itself a way that Gaines reclaims religious oppression in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. Instead of turning to God, she turns to another form of spirituality. She doesn’t visit a preacher, go to church, or even pray by herself in an empty room. She turns to Hoodoo instead, a form of spirituality that she didn’t even truly believe in, which becomes evident to the reader when she explicitly says, “I didn’t believe in hoo-doo, I never have, but nobody else wanted to listen to me.” A common belief in Christianity is that prayer is the quickest way to get God to hear you; yet, Jane felt like she didn’t have anyone who would listen to her. She wanted to visit a real person, even if she didn’t believe in the Hoodoo religion, because she knew that Madam Gautier would listen to her concerns. She didn’t have to doubt Gautier’s existence – she was tangible and directly in front of her.

I choose to interpret this scene of religious defiance as Jane doubting the existence of a God, but it could also be seen as her simply not being familiar with the Christian religion as a whole. Either way the reader interprets it, it can be seen as Gaines’ way of reversing the idea that Christianity was salvation for former slaves. He doesn't frame religion as something that can save her. In fact, Jane doesn't turn to Christianity at all. She turns her back on the wolf in sheep's clothing, choosing a different religion to find salvation in—and ultimately still failing to find that salvation.

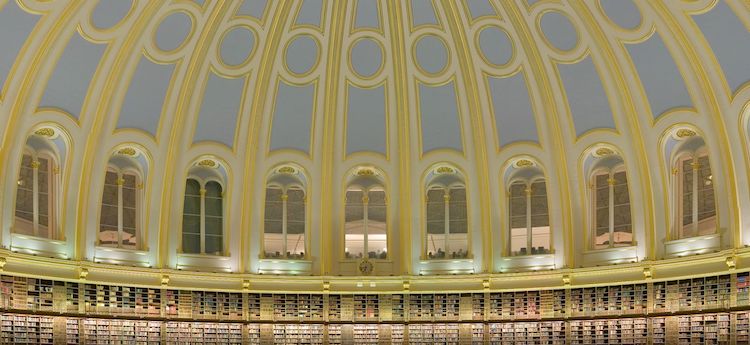

Going through the handwritten and typed drafts of the novel at the Ernest J. Gaines Center in the University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s library reveals that little to nothing was changed in this chapter. The content itself is relatively the same in both handwritten and typed drafts as it is in the published version of the book. The biggest difference lies in how the title of “Man’s Way” was rewritten a few times, changing from “The Fortune Teller” to “Man’s Fate” before ultimately ending up as “Man’s Way.” There were also no editor notes on the content in the chapter, showing that Gaines and his editor approved of the writing itself and the meaning behind it.

The idea that religion was salvation for slaves during the antebellum period has always been rooted in racist ideology. Because slave owners simply wanted to preserve both the social hierarchy they believed in and the entire institution of slavery in the southern United States, they decided that instilling religion into the enslaved masses was the best way to do so. Neo-slave narratives like The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, written with influence from both the Black Power and Civil Rights Movements of the 1960s, were created with the goal of shining a light on the religious oppression against enslaved peoples. Through the reversal of the meaning of Christianity in the pinnacle chapters of Gaines’ novel surrounding Joe Pittman's life and death and how Jane Pittman felt about it, he performed his own form of religious reclamation and truth-telling about antebellum slave narratives.

Works Cited:

Ernest J. Gaines, The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971).

Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene D. Genovese, "The Divine Sanction of Social Order: Religious Foundations of the Southern Slaveholders' World View" (1987).