Browse Exhibits (2 total)

London Fantasia

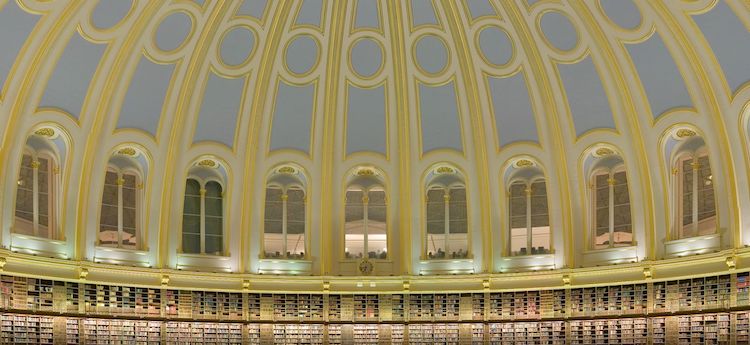

Nearly 200 hundred museums and over 350 public libraries, not to mention numerous galleries and research libraries, make their home in London, according to the World Cities Culture Forum. The United Kingdom’s capital city hosts an array of exhibitions that, taken in the aggregate, amount to nothing less than the Western world’s pinnacle of public culture. That achievement is not new, of course. Since the eighteenth century, Britain’s cosmopolitan center has led the world in building public educational institutions. Starting with the British Museum in 1753, the United Kingdom has added one jewel after another to its London crown of national culture. To name only the most prominent, those gems include The National Gallery (1824), The Victoria and Albert Museum (1852), The Science Museum (1857), The Museum of Natural History (1881), and more recently the Museum of London (1976).

Historical consensus suggests that the British investment in public museums and libraries changed the way we understand public institutions. Not only did that investment give London an unprecedented wealth of collections—enormous in scope and scale—but it also democratized access to them. National treasures became public treasures over the course of the nineteenth century. According to historian Michel Foucault, the dramatic growth of libraries and museums in that period invented a new space for human imagination to inhabit. “Fantasies are carefully deployed in the hushed library, with its columns of books,” he writes, “within confines that also liberate impossible worlds. The imaginary now resides between the book and the lamp.” With so much of the world’s knowledge organized into library collections and museum exhibits, it makes sense that much of the world’s imagination would develop from those same spaces. Institutions such as those named above preserve national and international traditions, document broad swaths of human knowledge, and give us narratives of civilization that run from prehistoric times to our contemporary moment. In doing that work, they also testify to the legacy of imperialism that allowed the United Kingdom to extract, accumulate, and command such extensive resources from all over the world.

In the aggregate, the museums and libraries of London present such an awesome collection of materials that no single project could hope to account for all their nuances and contradictions. Instead, this digital exhibit uses London’s vast treasures to draw out some of the minor themes, counternarratives, and unsung attributes running across institutional collections big and small. The authors of these exhibit essays highlight materials from the most notable museums and libraries in London, such as Tate Modern. At the same time, they also highlight some of the city’s cultural exhibits that tend to get excluded from discussions of its museum culture, such as instances of fan art and the Blue Plaques marking English heritage sites. The result is a diverse collection of small exhibits that bring to our attention the various paths patrons can travel through London’s cultural history. These authors traveled those paths through institutional and imaginary spaces.

Reading Miss Jane Pittman Now

The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman put Ernest J. Gaines on the national literary map when it came out in 1971. It arrived amid public debate about literary representations of slavery. A few years earlier, white author William Styron published what has come to be called a neo-slave narrative with his novel The Confession of Nat Turner. Many readers found it offensive in its depiction of enslaved people and dubious in its historical claims about Nat Turner. Miss Jane Pittman offered a sort of corrective that grounded an entirely fictional main character in rigorous historical realism.

Preceding other well-known neo-slave narratives like Roots, Kindred, and Beloved, Miss Jane Pittman paved the way for urgent reconsideration of the historical legacy of chattel slavery in the United States. Gaines’s novel tells the life story of a 110-year-old woman born into slavery who lives long enough to see the Civil Rights Act of 1964 become law. The title character survives all manner of indignity and injustice, from the failed promise of Reconstruction to the assassination of her closest kin. The hundred-year narrative arc raises the question, did the Civil Rights Movement finally deliver on the promise of freedom?

That question remains open even in 2022. Indeed, we are living through a historical moment with distinct echoes of the post-Civil Rights moment. After the police-murder of George Floyd in 2020, we saw the largest eruption of anti-racist protests since the 1960s, not just in the United States but all over the world. By the fall of 2022, however, the call to restructure the relationship between police and the people, to redistribute the wealth built through exploitation, and to repair the centuries-long impacts of racial violence gave way to corporate sloganeering. No longer even an assertion that Black lives matter, the movement became the anodyne hashtag #BLM. Yet, even now, the work toward justice continues, even if under new banners or in less-publicized venues.

The essays collected here reflect on Miss Jane Pittman from the perspective of our current moment. They consider not just the legacies of enslavement, Jim Crow segregation, and the Civil Rights Movement but also the possibility for a meaningful reckoning under our current social and cultural regimes. How is the racial past inscribed in our landscapes and our built environments? How does race intersect with gender, class, and religious belief? How do folkways and regional vernacular preserve otherwise marginalized cultural forms? These concerns and more organize this collection of critical reflections on Miss Jane Pittman. Despite all the reasons for a pessimistic view of the half-century since the novel came out, the contributors here find productive, even provocative reasons for revisiting this historically significant novel in our current moment. We hope these essays help other readers have a similar experience of reading Miss Jane Pittman now.