A Folktale in the Making: The Tragedy of Tee Bob

By Nashia Karim

Of all the anecdotes making up The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, it is the third section of the novel that feels most like a folktale. It is about the tragic love of Tee Bob for Mary Agnes LeFabre told through the eponymous Miss Jane Pittman. In earlier drafts, author Ernest J. Gaines concluded it as a letter but this became a deeper dive into the exclusivity of New Orleans Creole community and the fraught dynamics of interracial desire. In both versions, the story is told through multiple narrators to enhance its credibility—included are many direct quotes from eyewitnesses. The collecting of such accounts provides a good format for how to bring into existence a folk tale within a community like the Samson plantation.

As a primary source, Miss Pittman had access to Tee Bob and Mary Agnes since she was a housekeeper and landlady to each respectively. The gaps she was unavailable for are provided by other members of the community in the Quarters and in the Samson House. In the novel, Miss Pittman could gather everyone’s accounts into one coherent narrative in the form of a folk tale that can be passed down to future generations of their community.

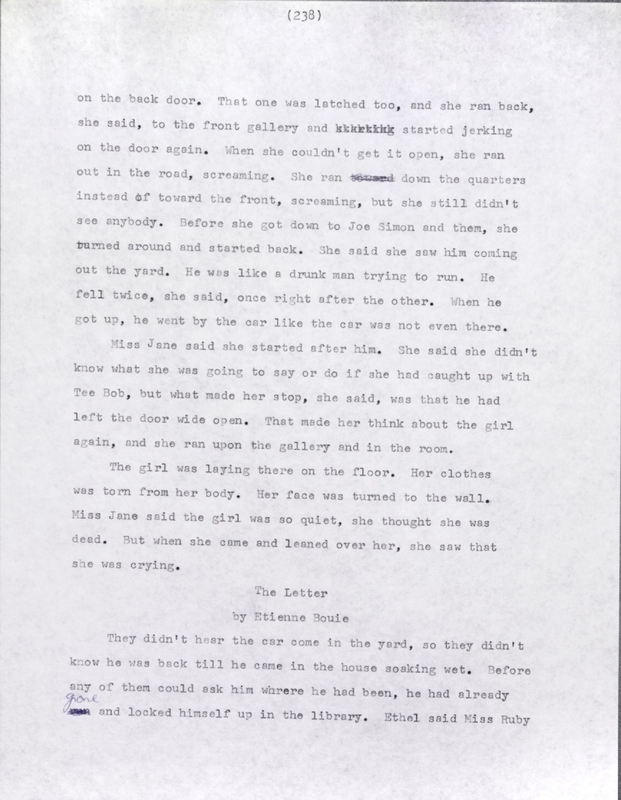

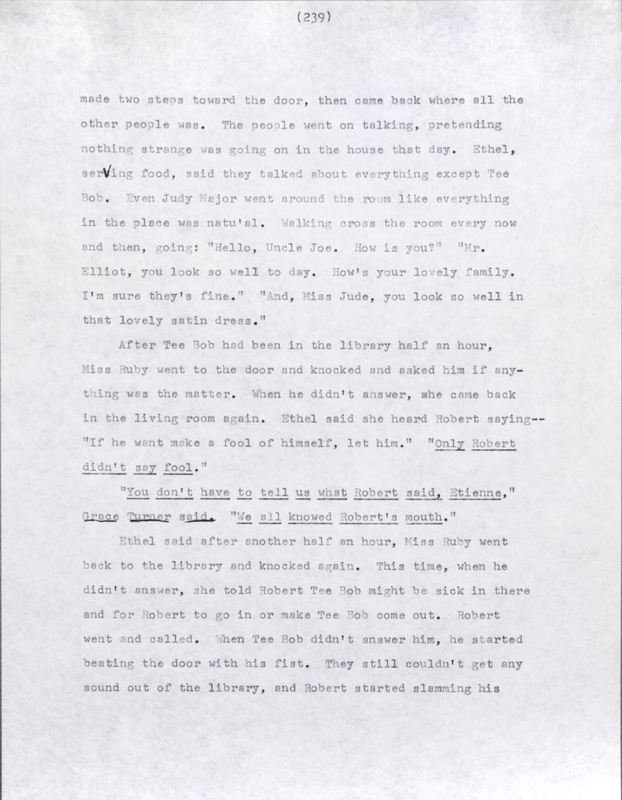

The tragedy of Tee Bob was completed as a “Letter from Etienne Bouie” in initial drafts. The letter starts (the first draft image) after Tee Bob runs away from assaulting Mary Agnes, something he explicitly does not do in the novel. In the letter, Ethel and Miss Jane Pittman are the prime witnesses Etienne Bouie cites. Both Ethel and Miss Jane quote the people they see such as Robert Samson, Miss Judy (who seems to become Miss Amma Dean in the novel), and Jimmy Caya. In the novel, the narrator is always Miss Jane Pittman and it is she who recounts what she heard from other sources whenever she wasn’t present.

As a folktale, the story highlights the rules of Miss Pittman’s world, the different communities that make it up, and the consequences of breaking their boundaries. The rules are inherited and maintained by all members of society – making them complicit in the tragic consequences of the rule breakers. Tee Bob’s suicide can be seen as either a brave resistance to harmful traditions or as a way for society to get rid of its too rebellious members. In case of the latter, Tee Bob becomes an example to potential dissenters in the community. Like a good folk tale, the moral of the story is outlined by Jules Raynard to Miss Pittman near the end—there is no space for men like Tee Bob who defy society.

Throughout the tale, the community members are keenly aware of the social rules of decorum. For Miss Amma, acknowledging that her rich white son could love anyone who was not white was an impossibility. This made her shut down the convivial conversation about Tee Bob with Miss Pittman and Robert. Afterwards, Clamp is too rooted in social rules to be effectively helpful—he does not go in to check up on Mary Agnes though he was worried about her after he saw Tee Bob running away from her house. When Clamp calls for help, Joe Simon wants to do nothing about it and tries to prevent his wife Ida from going to Mary Agnes’ aid, who he wants to believe brought the assault upon herself. Becoming involved in the accidents of their master’s son might have dire consequences for these folks in the Quarters.

This social awareness is also striking in the letter where Ethel is remembering Tee Bob’s father’s reaction. Underlined in the second picture of the draft, Ethel says, “Only Robert didn’t say fool” and her interlocuter Grace Turner responded with, “You don’t have to tell us what Robert said, Etienne, […] We all knowed Robert’s mouth.” This censoring of the story is accepted by the listeners—they knew their master too well and how the same rules didn’t apply to them. This interchange is absent in the novel, replaced by Clamp’s ineffectual attempts to get help for Mary Agnes.

The tragic story of two nonconformists is a good example of a folktale that allows Quarters folk to ponder over. The story brings the three different communities into exchange with each other to discover what the social limitations are imposed on them are—narrator Miss Pittman is always hesitant from interfering too directly into the story as do Clamp and Miss Amma Dean, despite their anxieties about the situation while dignified Mary Agnes must rely on Tee Bob’s decency from repeating Robert Samson’s example. After the expulsion of the rebellious elements of society (with Mary Agnes forced to leave the plantation and Tee Bob dead), each community looks back upon what could have led to a better outcome.

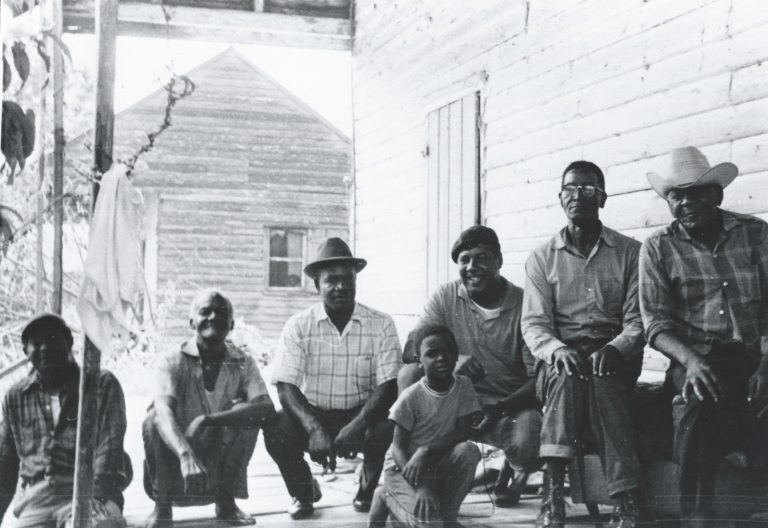

The style of the story itself was probably inspired by folktale traditions Ernest J. Gaines grew up with. For his writing projects, Gaines would return to Louisiana from his residence in San Francisco. “When I was writing this book, I did a lot of research. I did a lot of reading in history, by black as well as white historians. I read a lot of black folklore. I read a lot of interviews with ex-slaves, the WPA interviews with ex-slaves in the Thirties” (Tooker). It could be that one of these conversations such as shown in the photograph could have inspired the story itself.

The onlooking black community of the Quarters who witnessed and presented their sides of the story for fireside discussions take away the lesson of how social change requires patience. As a folk tale, Tee Bob and Mary Agnes serve to teach its different audiences the dangers of changing too fast or not enough—a lesson taken to heart by Miss Pittman before she engages in her own social protests after Jimmy Aaron’s death in the final part of the novel.

*Tooker, Dan, and Roger Hofheins. “Ernest J. Gaines.” Conversations with Ernest Gaines, edited by John Lowe, University Press of Mississippi 1976, 99-111.