The Landscape Remembers, Too

By Amélie Broussard

America's history of slavery doesn't just go away if we choose not to think about it. It's built into our environment; the White House, the Smithsonian, Georgetown University, and countless other buildings representative of freedom and upward mobility were constructed by enslaved people. These buildings hold the—often uncomfortable—truth about the history of our nation. America was built for white people by those they enslaved. While these buildings are beautiful, the people who built them deserve recognition for their contribution too. The characters in Ernest J. Gaines' The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pitman are unable to escape the history of the spaces they inhabit as they live out the South's brutal reiteration in slavery in a post-Emaciation Proclamation Louisiana.

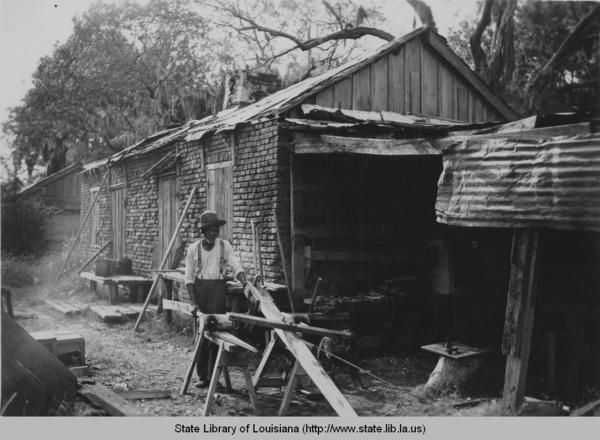

Shadows of slavery abound everywhere in Miss Jane Pittman. From the tangled, wild swamp young Miss Jane and Ned traverse when first leaving their enslavers to Tee Bob’s interactions with Mary Agnes, the characters struggle to free themselves from the lasting impressions of slavery built into their environment. The physical landscape does not change with the emancipation proclamation as formally enslaved people struggle to reshape their relationships in the wake of the ending of formal slavery without any physical markers of change. Some newly freed people remain on the same land they were forced to tend through slavery, but for those who choose to leave—like Miss Jane and Ned—the landscape acts as a sticky place of entrapment, forcing them to cut their escape from the South short. Even when Ned leaves for the North, he eventually finds his way back to his roots in south Louisiana. Furthermore, many white people hold on to the crumbling and rotting remnants of the “Old South,” clinging onto hope that these shadows can be brought back to life. Tee Bob crumbles under the weight of knowing his ancestors are responsible for the racist society they still live in. Furthermore, he commits some of the same atrocities upon Mary Agnes that plagued both of their families for generations. Formally enslaved people remain farming the same land, living in the same plantations, and even working for the very same families that brutalized their ancestors. Their society is built on a hierarchy of separation based on racialization and constructed during slavery. The psychic damage of slavery surrounds white and black people alike in the fields, plantations, and swamps around them.

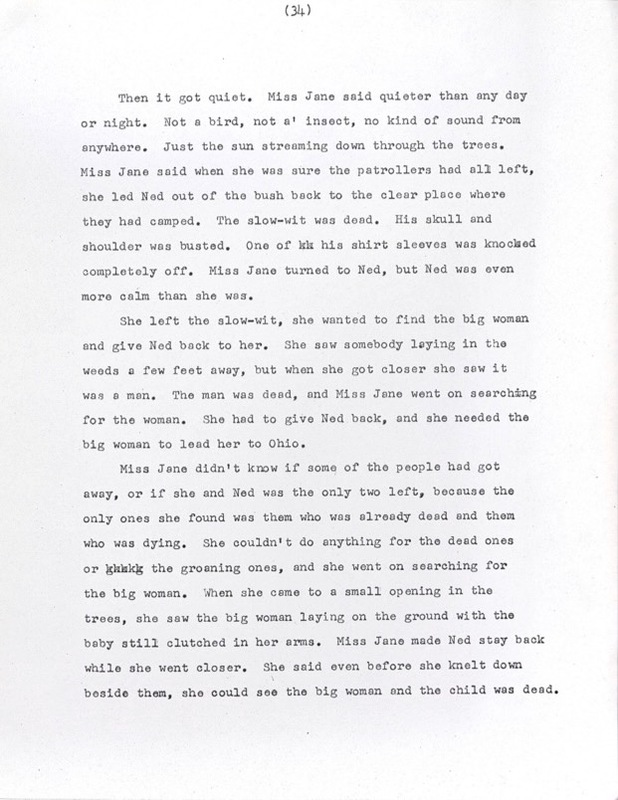

When news of emancipation comes to Miss Jane’s plantation, the formally enslaved people are divided about whether to stay or go. In a scene from Gaines' published novel, one of the young people desperate to leave says, “They got blood on this place, and I done stepped all in it. I done waded in it to my waist. You can mend a broken heart, you can’t wash blood off your body.” The history of the violence of slavery mars their vision of the plantation. For Miss Jane and the others attempting to travel to the North, there is no way to wipe the memories of the horrors of slavery from the physical location it occupied. Very shortly after they leave the plantation the group encounters Patrollers in the swamp. They all scramble to hide in the bushes, but the landscape does not protect them from their attackers. Miss Jane is forced to helplessly watch as her companions are brutally beaten to death while she and Ned also hide in a bush; somehow, she and Ned are missed by the Patrollers. Even the swamp recoils at the gratuitous violence. In one of Gaines’s prepublication drafts of Miss Jane Pittman, he emphasizes the shock of this violence reflected in the landscape: “then it got quiet. Miss Jane said quieter than any day or night. Not a bird, not a’ insect, no kind of sound from anywhere.” Although the swamp may seem sympathetic here, the land typically functions as a barrier in the lives of formally enslaved people in the novel, leaving them unable to truly move on with their lives after being "freed."

Unsuccessful in their attempts to reach the North, Miss Jane and Ned end up working on a plantation not far from the one where they were born. Institutionalized white supremacy ensures that the swamp around this plantation is still fed a steady diet of black bodies. White men patrol the swamps around the plantation and fields on horseback to ensure the people working there are unable to escape the quasi-slavery conditions. Miss Jane talks about a bayou that “got more people in it than a graveyard,” which was too wide and muddy for fleeing black people to wade across to get away from the patrollers and their dogs. This “Dirty Bayou” serves as a daunting obstacle for Miss Jane and the other workers if they were to ever decide they wanted to flee. If they were to leave, the owner of the plantation makes it clear that he would ensure they would be relentlessly chased and killed for their transgression. Even after the emancipation of formal slavery, the land continues to be soaked in the blood of black people, and Miss Jane remains stuck in the muddy swamp, dirty bayous and all.

For white people in the novel, the buildings they inhabit are constant reminders of their family’s past as brutal enslavers. The Samson plantation and quarters embody a sense of a hidden, horrific past. Tee Bob is unable to come to terms with the racist society he has been born into. He does not understand why his father, Robert, treats his half-brother so differently because he is mixed race. Robert feels like the racial hierarchy built into their society is “part of life, like the sun and the rain was part of life, and Tee Bob would learn them for himself when he got older.” Tee Bob goes on to fall in love with Mary Agnes, a mixed-race schoolteacher on the plantation, who also understands the history of racism built into their society. The history of slavery seeps into their relationship.

When Tee Bob tells his best friend about his love for Mary Agnes, Jimmy echoes Robert’s view about the inevitability of their racial hierarchy. He says Tee Bob cannot date Mary Agnes, but that he can “take her” whenever and how ever he wants. Jimmy is clear that he did not make these social conditions but that was “what everybody had always told him. From his daddy to his teacher had told him.” Tee Bob has no way to escape the beliefs that force him apart from his love; they emanate from the very home and land he inhabits. Tee Bob’s ambivalence about the racialized society he lives in comes to a head when he goes to Mary Agnes’ house to ask her to run away with him. When Mary Agnes refuses to run away, time collapses and he attacks her in the small house she lives in on his family’s plantation —formally the slave quarters—and “the past and the present got all mixed up.” Although he loves her, the history of what happened in that space remains, as he embodies his own father forcing himself upon Verda or the “Creole gentleman” who forces himself upon Mary Agnes’s own grandmother. The physical space of the slave quarters brings with it the historical reality of the treatment of many black enslaved people at the hands of their white enslavers. Mary Agnes has no choice but to embody the disfranchised, powerless women that litter her family tree. There can be no pure love between black and white people on Samson plantation, not only because of the attitudes of the people who live there, but also because of the history of the place itself.

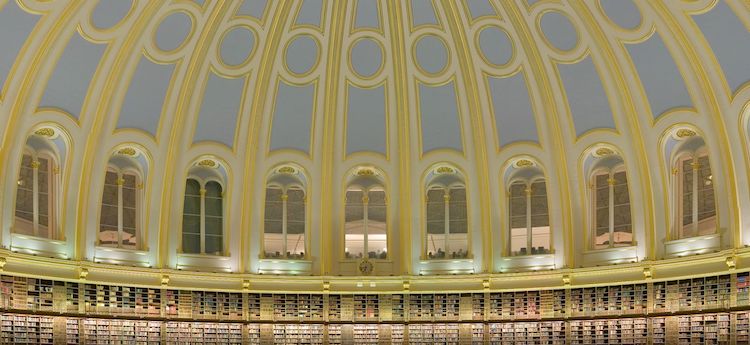

Tee Bob runs away from Mary Agnes back to the big house and locks himself in his grandfather’s library. Here, too, the imprint of slavery and racialized violence seeps out of the walls. The library was full of the remnants of racialized violence, filled with books on history and slavery itself. He feels like he can hear “the sound of his grandfather talking to his daddy and his uncle come out every wall.” The room was full of memories and reminders of the macabre, racist imprints of the conversations that happened there. Tee Bob is unable to escape the memories of his family’s racialized atrocities and his own contributions to that violence because they surrounded him on all sides in that room. Unwilling to succumb to what he feels is his predestined life as a white man in the deep south, he chooses suicide as his way out. The tragedy of Mary Agnes and Tee Bob’s love story is part of the much larger impression that slavery left on relationships between white and black people. While they remain in the spaces that witnessed the brutalities of this “peculiar institution,” they are unable to escape the reminders of violence and power hierarchies etched into the landscape. Much like the “Dirty Bayou” that served as a place of entrapment for formally enslaved people trying to leave their harsh work environment, the violence of the past remains in these buildings and seeps into the people who still live in them.