Performing Medicine: Audiences to the Human Form

This exhibit explores the relationship between performer and audience in the medical world. It also serves as a timeline for the evolution of this relationship from the beginning of public surgeries to the modern operating room. Is it possible to separate performer and audience member in the medical world? Does modern medicine remain a performance? How has this relationship changed over the years, through medical advances? This exhibit endeavors to answer these questions by contextualizing, comparing, and contrasting each artifact.

What connects these four artifacts is aesthetic likeness and purpose. The cover page for Andreus Vesalius' De Humani Corporis Fabrica is one that depicts the operation as a spectacle; the drama and audience of the operation are more prevalent than the operation itself. The grim reaper and the cherubs depicted in the cover page are more romantic symbols than necessary for the cover of an anatomical textbook. The pillars of the building surrounding the scene are curved, further creating the effect of a theatre in the round. The purpose of this cover page is to convey the necessity of an audience; it connects humanity with what is intellectual and scientific. The drama and emotion of the image ground it in humanity, while the contents of the book deal with fact, medicine, logic, and science.

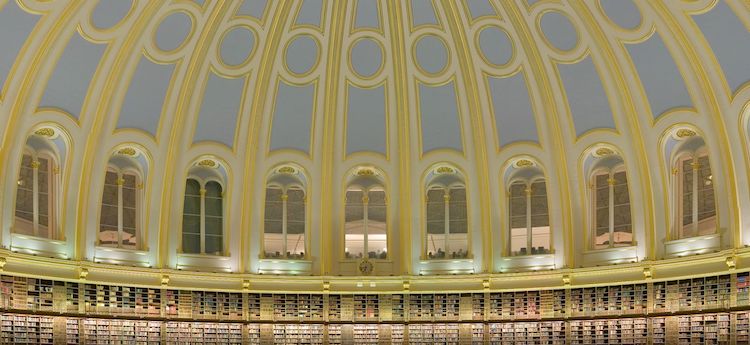

The Old Operating Theatre is the reality of De Humani Corporis Fabrica; it is a manifestation of the idea that medicine necessitates an audience. Space for onlookers is built into the operating theatre. The space for audience members seems to almost take precedence over the space for the surgical proceedings, revealing the priorities of the medical world at the time. It may have seemed just as important to have an audience as it was to do the surgery itself. The operating space closely resembles a theatre in the round, complete with costumes, props, and stage doors. The tools used during these proceedings are as practical as they are grotesque.

"The Operating Room and the Patient" completes the timeline of performer and audience within the medical field with an example of a more modern operating room. The space for audiences is less apparent in this image, yet there are still the props and staging of the previous two artifacts. The lights, for example, illuminate the work at hand but are also reminiscent of lighting used in productions like Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street. The props and customs of the medical performance have been formalized and established, there is now a set ritual to the art of surgery. The drama of this performance, while still present, has been somewhat separated into the world of the arts. Surgery is still a performance. It is a ritual with audience members, props, and set deisgn, but it is far from the initial depiction of De Humani Corporis Fabrica. The emotion and drama of the cover page is lost in "The Operating Room and the Patient," yet the image most closely resembles the stage of Anthony Ward's Sweeney Todd.

The last artifact is the extreme of the four; it is a performance space built to exhibit the most gore a theatrical show can offer. It is also slightly rounded, like the building of De Humani Corporis Fabrica. The space for carnage is small and placed in the center, much like the Old Operating Theatre, surrounded by the bleak grandeur of the stage. The tools, or props, used by Sweeney Todd's character, are similar to the tools used in the Old Operating Theatre; the weapon of choice is a straightedge razor often used to cut human flesh. Plays like Sweeney Todd: Demon Barber of Fleet Street offer a place for audiences to witness on the gore of the human body from a comfortable distance. The spectacle of the show hinges on its violence on the human form; the show relies heavily on the horror of bodily carnage. Sweeney Todd, like the cover page of De Humani Corporis Fabrica, connects what is human, or the arts, with that which is horrific and bodily.

The ingrained space for audience in each work or lack thereof as well as the merging of that which is medical, factual, and intellectual with the emotion and humanity of an audience, is what connects these four artifacts. In each work, the space for operation is placed in the center, emphasizing its importance as a spectacle. This exhibit portrays the way in which different mediums perform the gore of the human body, as well as the ways in which these artifacts convey the necessity of an audience to the violence or dissection of the human body.

These artifacts also provide a timeline of the progression of this performance. The performance of the dissection of the human body has evolved and changed from De Humani Corporis Fabrica, which melded the audience and performer together within the operation. As depicted within the cover page, the operation is within the audience space. These spaces are separated within the Old Operating Theatre, yet the audience still surrounds the operation. The space for operations now resembles a small stage surrounded by audience members, leading to the third and final artifact. The spaces are further separated within Sweeney Todd, where audiences watch the destruction of the human form on a true stage. While surgery today still remains to be a performance in many ways, the divide between audience member and performer has deepened. Costume, physical space, and years of training and medical school divide the two entities, yet they are still linked through the spectacle. Medical TV dramas and reality medical shows are in constant demand. The human form seems to demand an audience; see shows like Grey's Anatomy, House, ER, Embarrassing Bodies, Dr. Pimple Popper. Operating theatres are still in use. The fascination with the grotesquerie of the human form has persisted throughout the timeline of this exhibit, and still survives today.

The relationship between audience member and performer in the medical world are still linked, although the divide has grown since the creation of De Humani Corporis Fabrica. This exhibit explores the relationship between audience member and performer in the medical world through time. There is often space for audience members built into modern surgical facilities. Observation decks are built into teaching hospitals and are similar to the space provided in the Old Operating Theatre. Medicine and audience still share a strong relationship but have since evolved from the drama of De Humanis Corporis Fabrica to modern television dramas, as well as dramas like Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

Katie Clack