Art As Religious Instruments by Chris Cooper

In all cultures, people strive to understand their reason for being and their place in the universe. Often times, this reason for being and universal understanding is placed in holy figures, or gods. Beings that made us, control our fate, watch over us, care for us. Throughout history, the Gods that each respective culture sought meaning in have varied, along with what all they stand for and what they can control. However, these cultures all share in the fact that they’ve employed art in their worshipping of these higher powers. Art can be an instrument for not only recording spiritual beliefs and practicing them, but also for creating myths, defining the realms of mortal and immortal, communing with ancestors, channeling forces of good, and repelling those of evil. This religious art comes in many different forms; whether it be a sculpture made in the likeness of Zeus for the mortals to praise and give thanks to, a feathered bonnet for the sake of "flying" and hoping to view the world as the gods do, or a temple reaching up to the sky in hopes of communicating with Kukulcan, these all share in their function of praising, pleasing, and seeking to maintain good standing with their culture’s respective gods.

The workings of the heavens are made transparent at Chichén Itzá. El Castillo has been precisely aligned so that on the annual spring and fall equinoxes, the light of the setting sun creates a series of shadows running down the north side of pyramid. These triangular shadows merge with the carved head of a serpent at the pyramid’s base, forming what looks like the body of the reptilian creature. As the light changes, this serpent seems to slither down the pyramid and off toward the sacred cenote, a natural sinkhole considered by the Maya to be an opening to the Underworld.

In Maya mythology, the notion of the feathered serpent that can move between worlds was associated with the god Kukulcan. One of the "creator deities", Kukulcan was linked with resurrection and rebirth and was believed to have brought civilization to human beings in the form of art, calendars, and agriculture, among other things. Various images of the feathered serpent can be found at Chichén Itzá and since at least the sixteenth century, El Castillo has also been referred to as the Temple of Kukulcan. The descent of the serpent on the occasion of the equinox may have symbolized the beginning of the agricultural cycle and the renewed life it implied.

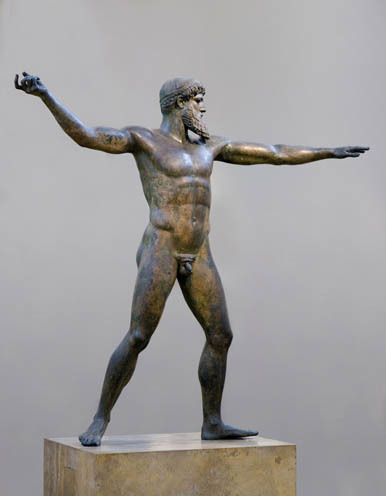

Meant to be seen from one ideal vantage point—standing facing the vast and muscular torso—this three-dimensional figure demonstrates complete mastery of anatomy. From the intense expression on his face, the bulging veins of his feet, and the variegated transitions between muscles, Zeus appears to be rendered from a human model. However, on closer examination, it is clear that aspects have been simplified and proportions expanded to give the figure the exemplary body worthy of his divine status. The sculpture, which presents its subject as superhuman rather than suprahuman, is in keeping with the Greek conception of gods as immortal and immensely powerful, yet subject to the personality flaws and unpredictable emotions of mortal beings.

The Kayapó believe that they originally lived in the upper layer of the universe, but descended to earth through a circular opening at the bottom. The circle is referenced not only in headdresses like this one, but also in other cultural productions.

The heart of the Kayapó village is its innermost ring, a large open plaza containing the men’s house where the headdresses are donned and social/ritual activities take place. The kind of ceremonial dances and performances that occur in this arena are referred to in Kayapó as “flying.” Furthermore, many rituals involve songs in which performers associate themselves with birds. In this context, the wearing of feathers in ceremony takes on a deeper significance. To fly like a bird is to rise above the ordinary world and get a glimpse of the larger picture, the universe in its totality.

As made evident by the examples above, the way different cultures seek to understand their reason for being and their place in the universe varies, and this variation in style is reflected in their religious art. The Greeks commonly sought to please the gods by erecting glorious, personal sculptures and temples in their likeness, the Mayans sought to create pathways between heaven, earth, and the underworld both for themselves and the gods, and the Kayapos sought to recapture higher ways of thinking and glimpses of the outer universe where they once dwelled. Despite these differences, however, what remains the same is their shared utilization of art as an instrument for practicing religion.