Bending Boundaries: Artefacts Outside of the Institution

Much of our perceived value of art, both individual and societal, is largely based on factors outside of the artefact itself: the amount of people who stop to snap photos of it, the price tag, the general popularity, the environment in which it is displayed, and, ultimately, the exclusivity of the institution. We depend on institutions and the people who run them to curate exhibits for us – to tell us both what is significant and why it is significant. We trust museums, as institutions, to collect and show us things that are deemed important, so we spend money on their carefully-set admission costs, we queue in lines, we face throngs of tour groups in tight spaces to explore buildings full of art that surely must be worth the obstacle. But many of the most meaningful experiences I have had with art have been outside of the walls of the institution – outside of the context of a museum.

In every city are hidden gems. Some are tucked out of the line of vision, high up with the summits of skyscrapers or below in metro tunnels under busy streets; others camouflaged in plain sight, overlooked between the hustle and bustle of quotidian routine.

By breaking through the boundaries of “valuable” artefacts’ expected display standards, we can begin to experience art differently, and develop our opinions more subjectively.

Challenging traditional definitions of art, and the institutions or venues that host it, allow us to rediscover our immediate surroundings and reconsider art’s assigned value.

After all, these pieces that fill museums all once existed elsewhere. Is it not, then, the highest privilege to view art and artefacts at their place of origin, not yet affected by the imposed values that come with the exclusivity of the institution?

Secret Diary of Bloomsbury

Beginning with the intentionally hidden, the Secret Diary of Bloomsbury quietly nests inside of a birdhouse perched on a post along the Russel Square sidewalk. A block from our London hotel, in a public park, the piece wills passersby to open it up, to look inside, to leave a message of their own. This series of diaries has ascribed artistic worth, but instead of a hands-off approach, it exists in a way in which people can and should interact with it. It is both a community public record of the Bloomsbury neighborhood and a collaborative art piece, giving it both cultural and historical value.

Stapled onto the cover of the journal inside of the birdhouse is a form of artist statement, explaining the what and the why, and giving the user instructions for participation.

This series’ purpose is intrinsically tied to its secrecy, and if it were to be displayed in a more obvious manner, or in a more official venue, it would lose much of its effect. It ultimately could not exist in a meaningful way inside of a museum. The diary is meant to be unearthed – to be lost in the humdrum and to be found right under the noses of only the actively observant park pedestrian.

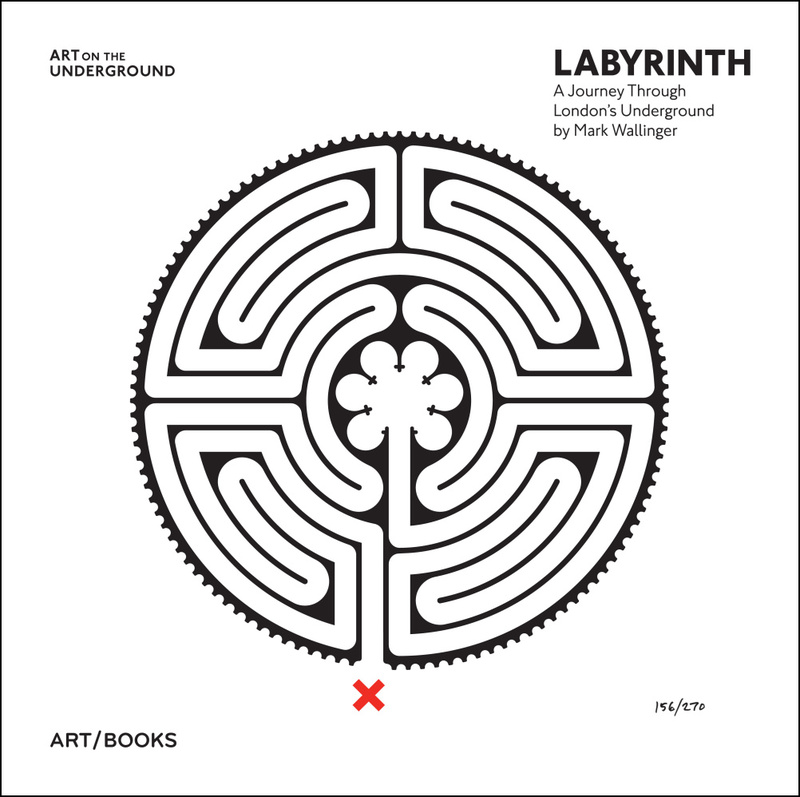

Labyrinth

Other pieces, such as the London Underground Labyrinths, are absolutely intended to be seen and are thus placed in plain sight, but are rarely observed as more than a blurred detail in the watercolor landscape of the daily London routine. These 270 labyrinths by Mark Wallinger occupy each of London’s tube stations, each one with its own unique geometric design. Yet despite the thousands of people that pass them by each day, they go mostly unnoticed. If they were displayed outside of the context of the subway, though, they would lose the artist’s intended metaphorical meaning as a representation of the “daily journey commuters embark upon while traveling through the city.” Commissioned in the 2000s to commemorate the Tube’s 150th anniversary, this series, to serve its purpose, must exist outside of the museum, and inside the maze of the London underground. Its meaning, and thus its value, is directly tied to the place in which it is displayed: in the crowded, tight-scheduled, stale-aired, throbbing and thrumming veins of the metro.

Wallace Fountains

Another example of government-commissioned artwork outside of the walls of a museum — this time in a different European metropolis — is the Paris Wallace Fountains.

These eighty-some water fountains serve a dual purpose of aesthetic and functional value. They are recognized worldwide as one of the symbols of Paris, but like the London Underground Labyrinths, are regularly overlooked in their place on the busy sidewalks of the city. In their great sculptural beauty, their functionality is hidden until actively observed by the attentive eye. There are different variations and sizes of these fountains – for the large model, sculptor Lebourg cast four caryatids representing kindness, simplicity, charity and sobriety. Each one of these sisters is different from the others, in the bending of her knees and the tuck of her tunic. The attention to detail is breathtaking when compared to any average public water spigot.

More respectable than its beauty, though, lies in its initiative to provide clean drinking water to Parisians of modest means since the 1870s, in a time when water was more expensive than alcohol, or else not safe to drink. Today, these carefully-sculpted cast-iron founts remain as one of the only sources of free water for the homeless. Their functional value would be all but lost in a museum, and their historical value much more meaningful in their original setting, still serving water to the masses after nearly 200 years of quenching the common man’s thirst. Even the aesthetic value could easily be lost if institutionalized, the caryatids seeming out of place, becoming dwarfed when lined up in white-walled halls alongside the Herculean sculptures of Cousteau or Canova.

London Blue Plaques

Sometimes a curated view of the public environment enables us to view our surroundings in a way that achieves a greater perceived historical and artistic value, as is the case with London’s Blue Plaques that can be seen scattered across all of the city’s boroughs. These 900-odd placques on their designated buildings honor notable former residents, many of whom were renowned artists. To see this touch of blue on a building’s façade calls to attention not only the artist themself, but all of the works created at their hand within those walls. Although there still exists the imposed boundary of curation in the display of these plaques – the selection of the people, places, and events that they recognize are carefully nominated and chosen – the “exhibit” as a whole is largely more accessible by the masses, viewable on well-travelled public streets, and thereby immersive by nature. The plaques bring preexisting structures to a different light, provoking a greater appreciation and respect for one’s immediate surroundings.

Palais de Tokyo LASCO Project

Some of the most stirring spaces are those that blur the boundaries between which works of art should or should not be institutionalized.

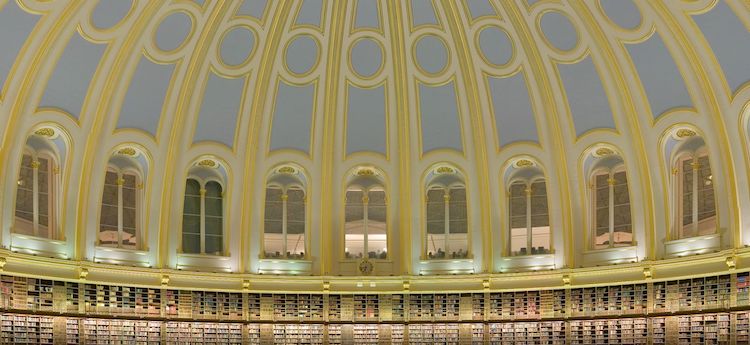

Out of sight and out of mind of the unsuspecting Palais de Tokyo patron weave corridors of a unique, titillating collection of urban art. For nearly a decade now, these subterranean passageways that snake behind the closed doors of the museum have served as an ever-evolving, striking collage of murals and art pieces by some of the world’s most renowned street artists.

Since its conception in 2012, The LASCO PROJECT has only been accessible via guided tours organized by the museum. Even so, these tours maintain an air of secrecy – when I participated in one, I was one of only two attendees, with the tour guide bringing our grand total to three. New artists are invited each year to add to the collection, with a tally of over 60 participants thus far, but the most compelling aspect of the exhibit stems from the many uninvited, unrecognized artists at the project’s genesis. Before LASCO came to be, at the turn of the century, street artists of Paris would slither their way into the catacombs of the temporarily-abandoned building that is now Palais de Tokyo and leave their marks on the walls, hidden from the public eye – only accessible and only known by the artists themselves, and by the other members of their clandestine community. They used this then-vacant space as a secret gallery – sub rosa creating for the sake of creating, for the sake of practice, for the sake of protest, perhaps, or maybe just because they could.

Of course, these particular works were not brought to public light by any organization, despite having fueled the idea for The LASCO PROJECT. In 2012, around a decade after Palais de Tokyo’s opening, the publicly unknown maze of untouched urban art was reclaimed by the institution. The art that now fills its hidden halls is brought about by invitation, not invasion. The purpose of the space has been spun on its head, inverted through institutionalization.

The continuation of The LASCO PROJECT raises a number of questions about the results of the reclaiming of space and art by a museum or by any similar institution.

Are projects like this an evolution or a devolution of space, or a mind-boggling mixture of the two? Does this add to or take away from the “value” of the works that lie within?

Can art conceived in defiance be respectfully viewed and authentically appreciated through the structured boundaries of a guided museum tour? Or perhaps there are some forms of art that can only retain their intended value and meaning outside of the confines of the institution.

Carolina Chauffe