London Fantasia

Nearly 200 hundred museums and over 350 public libraries, not to mention numerous galleries and research libraries, make their home in London, according to the World Cities Culture Forum. The United Kingdom’s capital city hosts an array of exhibitions that, taken in the aggregate, amount to nothing less than the Western world’s pinnacle of public culture. That achievement is not new, of course. Since the eighteenth century, Britain’s cosmopolitan center has led the world in building public educational institutions. Starting with the British Museum in 1753, the United Kingdom has added one jewel after another to its London crown of national culture. To name only the most prominent, those gems include The National Gallery (1824), The Victoria and Albert Museum (1852), The Science Museum (1857), The Museum of Natural History (1881), and more recently the Museum of London (1976).

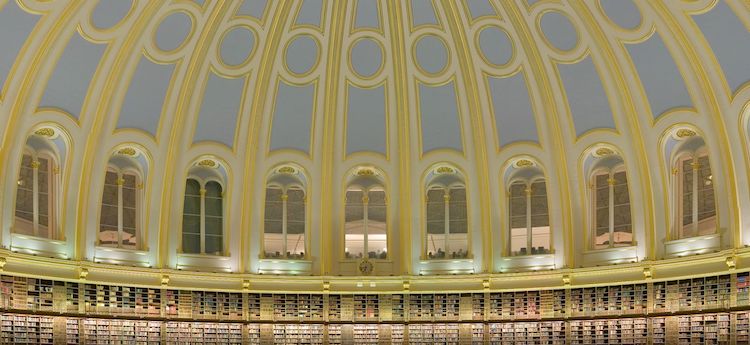

Historical consensus suggests that the British investment in public museums and libraries changed the way we understand public institutions. Not only did that investment give London an unprecedented wealth of collections—enormous in scope and scale—but it also democratized access to them. National treasures became public treasures over the course of the nineteenth century. According to historian Michel Foucault, the dramatic growth of libraries and museums in that period invented a new space for human imagination to inhabit. “Fantasies are carefully deployed in the hushed library, with its columns of books,” he writes, “within confines that also liberate impossible worlds. The imaginary now resides between the book and the lamp.” With so much of the world’s knowledge organized into library collections and museum exhibits, it makes sense that much of the world’s imagination would develop from those same spaces. Institutions such as those named above preserve national and international traditions, document broad swaths of human knowledge, and give us narratives of civilization that run from prehistoric times to our contemporary moment. In doing that work, they also testify to the legacy of imperialism that allowed the United Kingdom to extract, accumulate, and command such extensive resources from all over the world.

In the aggregate, the museums and libraries of London present such an awesome collection of materials that no single project could hope to account for all their nuances and contradictions. Instead, this digital exhibit uses London’s vast treasures to draw out some of the minor themes, counternarratives, and unsung attributes running across institutional collections big and small. The authors of these exhibit essays highlight materials from the most notable museums and libraries in London, such as Tate Modern. At the same time, they also highlight some of the city’s cultural exhibits that tend to get excluded from discussions of its museum culture, such as instances of fan art and the Blue Plaques marking English heritage sites. The result is a diverse collection of small exhibits that bring to our attention the various paths patrons can travel through London’s cultural history. These authors traveled those paths through institutional and imaginary spaces.

Credits

ENGL 370