I had a great time at MLA 2019 in Chicago. Between old friends and really, really good pirogi, I also managed to see some great panels, meet new colleagues, and catch up with the smartest folks in my field. I know a lot of people hate MLA, and for good reasons, but I look forward to it as a place to see all the people I miss seeing on the regular.

Below is the panel proposal that got me to Chicago this year. Looking forward to Seattle 2020.

The MLA Bibliography and Scholarly Editing Forum and the Libraries and Research Forum propose the collaborative session “Archaeologies of the Catalog” for the MLA 2019 Convention.

Throughout their history, catalogs have functioned in a variety of different capacities: they serve as access points to library holdings, document publishing or reading histories, or perhaps they detail exhibits or bookseller offerings. However, as scholars adopt newer data-intensive research methods, they are repurposing these catalogs and their digital descendants as sources of research data. Catalogs are consumed by scholars, not only to discover and access individual sources, but to mine their aggregate data in order to explore/expose patterns undetectable at human scale that might shed light on the history and sociology of texts and other catalogued materials. In this context, examining the work of cataloguing within its cultural, political, ideological, and technological contexts is crucial for situating the scholarly outputs of more data-intensive research methods.

Many scholars and cataloguers are approaching the work of cataloging as an opportunity to repair or (re)create publishing, reception, and cultural histories. This work builds upon work of early activists such as Sanford Berman, an early critic of biased Library of Congress Subject Headings. Although it hasn’t always been the case, librarians, archivists, and scholars today are less likely to make assumptions about the neutrality of our records, whether bibliographic or archival. We have finally reached the point where we, as a profession, recognize that the choices we make (whether structures, standards, descriptions, or what to include) are in fact non-neutral and carry assumptions, agendas, and biases.

In this session, our panelists continue this tradition and, in the process, echo what Foucault describes in his Archaeology of Knowledge: they consider artifacts that were included as well as those that we excluded, to examine the knowledge systems at work in order to re-map the whole. By exploring lacunae, erasures, and biases in catalogs and in the work of cataloguing, they seek to reconstruct and repair access as well as the historical context.

In her paper “Caribbean Periodicals and the Catalog: Toward Increased Accessibility and Impact,” Chelsea Stieber (Catholic U of America, DC) will illustrate the issues inherent to Caribbean periodicals in the catalog through her work with the the Revue de la société haïtienne d’histoire, de géographie et de géologie (RSHHGG), Haiti’s oldest and most prolific social science journal. Stieber reveals that this crucial repository of Haitian scholarly research remains opaque to traditional searching practices because the journal is not indexed, and thus rarely used and cited by scholars outside of Haiti. Stieber offers some new solutions to this problem with an interactive indexing project she developed in conjunction with the Labs program at the Library of Congress and National Digital Initiatives called the RSHHGGlab.

David Squires (U of Louisiana – Lafayette) will show how anti-lynching activists combated mob violence by achieving bibliographic control over ephemeral materials, ranging from local newspapers to real photo postcards. His paper, “Catalogs of Violence: Lynching, Bibliographic Control, and Black Modernism,” argues that the work anti-lynching activists did to reconstruct lynching records belongs to a genealogy of Black Modernism. Key figures such as Alain Locke, James Weldon Johnson, and Arturo Schomburg used bibliographic and documentary methods to establish the fact—and historical depth—of African American aesthetic achievement. Their documentary strategies worked to construct a positive archival footprint for marginalized Black cultures by drawing on bibliographic methods and a discourse of factuality that anti-lynching activists developed for recording violent erasures of Black life. The urgency of establishing bibliographic control over lynching records continues into the present, as the Equal Justice Initiative attempts to create a comprehensive inventory of lynchings in the United States. By turning to the earliest efforts to catalog lynching violence, this paper illustrates how bibliographic control can wed documentary and imaginative cultural practices.

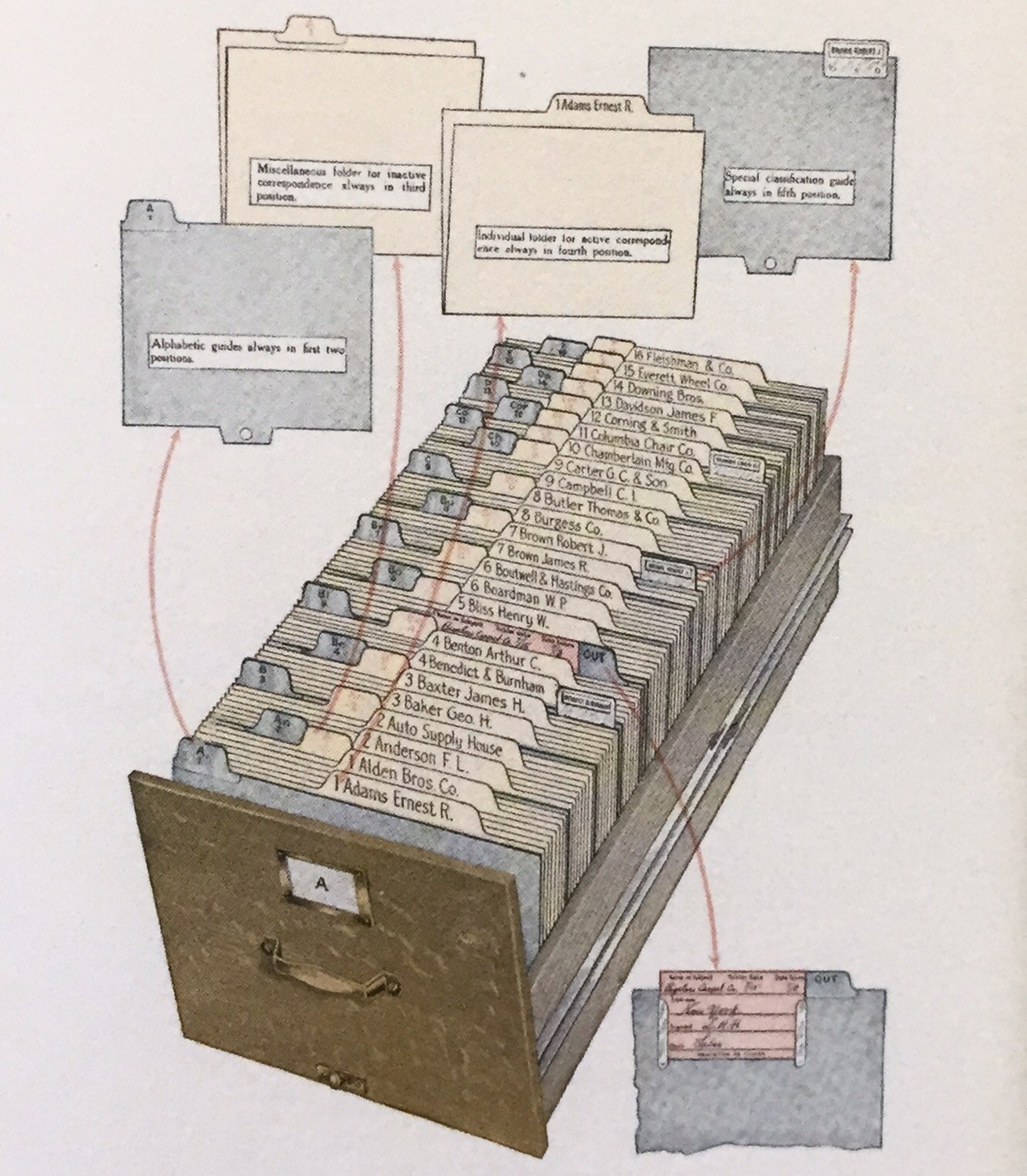

Laura Helton (U of Delaware) will discuss the cataloging work of Dorothy Porter, curator of Howard University’s “Negro collection” from 1930 to the early 1970s. Entering Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, one still passes through the “catalog room,” a small antechamber filled with neat stacks of wooden card catalog drawers—the kind most libraries have long since discarded. Inaugurated by Porter in 1930, this catalog room served for much of the twentieth century as one of the only portals to black print culture in the United States. The rise of electronic databases and full-text search has obscured the intellectual and imaginative infrastructure condensed in those 3×5 cards, but this paper will pause to consider such cards as critical artifacts in the history of information. For librarians like Porter, the card catalog was a site for challenging the routine misfiling of blackness in systems of knowledge. Understanding how Porter hacked the catalog–and how she rewrote Dewey Decimals and Library of Congress classification–has much to tell us about the way whiteness continues to shape information architectures and reading practices.

The session will be begin with a brief (~5 min) introduction to the topic by the session chair, including panelist introductions. Each panelist will then have 15-17 minutes to present their papers, followed by 20 minutes of unstructured discussion and Q&A.